Data Storage Fundamentals: Types, Architectures, and Scalability Considerations

Reader Roadmap and Outline

Storage quietly underpins every click, query, and dashboard, a backstage crew that rarely earns applause until a file goes missing or a latency spike steals the spotlight. This guide treats data storage as both craft and engineering discipline, helping you decide what to deploy, how to protect it, and when to evolve. To keep you oriented, here’s how the journey unfolds, with a practical focus for architects, developers, data leaders, and operators who juggle uptime and budgets.

We begin with a structured outline that doubles as a checklist. As you scan it, note where your current environment fits and where your plans might diverge. Use it to align stakeholders before you commit to new hardware, platforms, or policies.

– Section 2: Storage Media fundamentals. How HDDs, SSDs (including NVMe), and tape differ in latency, throughput, endurance, cost, and energy profile. We translate specs into workload impact, from boot storms to analytics scans.

– Section 3: Architectures and data models. Block, file, and object access patterns; DAS, NAS, and SAN placement; scale-up versus scale-out; and how consistency and metadata shape your application behavior.

– Section 4: Durability, protection, and governance. RAID versus erasure coding, snapshots and replication, the 3-2-1 backup principle, immutability, encryption, and operational guardrails for compliance and safety.

– Section 5: Scalability, performance, and cost. Caching and tiering, lifecycle policies, observability metrics, capacity planning, and a decision framework that ends with a concise, actionable conclusion.

Who should read this: teams facing rapid data growth, migrations, or performance tuning; builders designing new services; leaders writing next year’s budget. What you’ll get: trade-offs stated plainly, examples you can adapt, and a shared vocabulary to speed decisions. Expect a blend of technical depth and plain language, with the occasional metaphor to keep the pages turning—because even storage benefits from a little narrative structure.

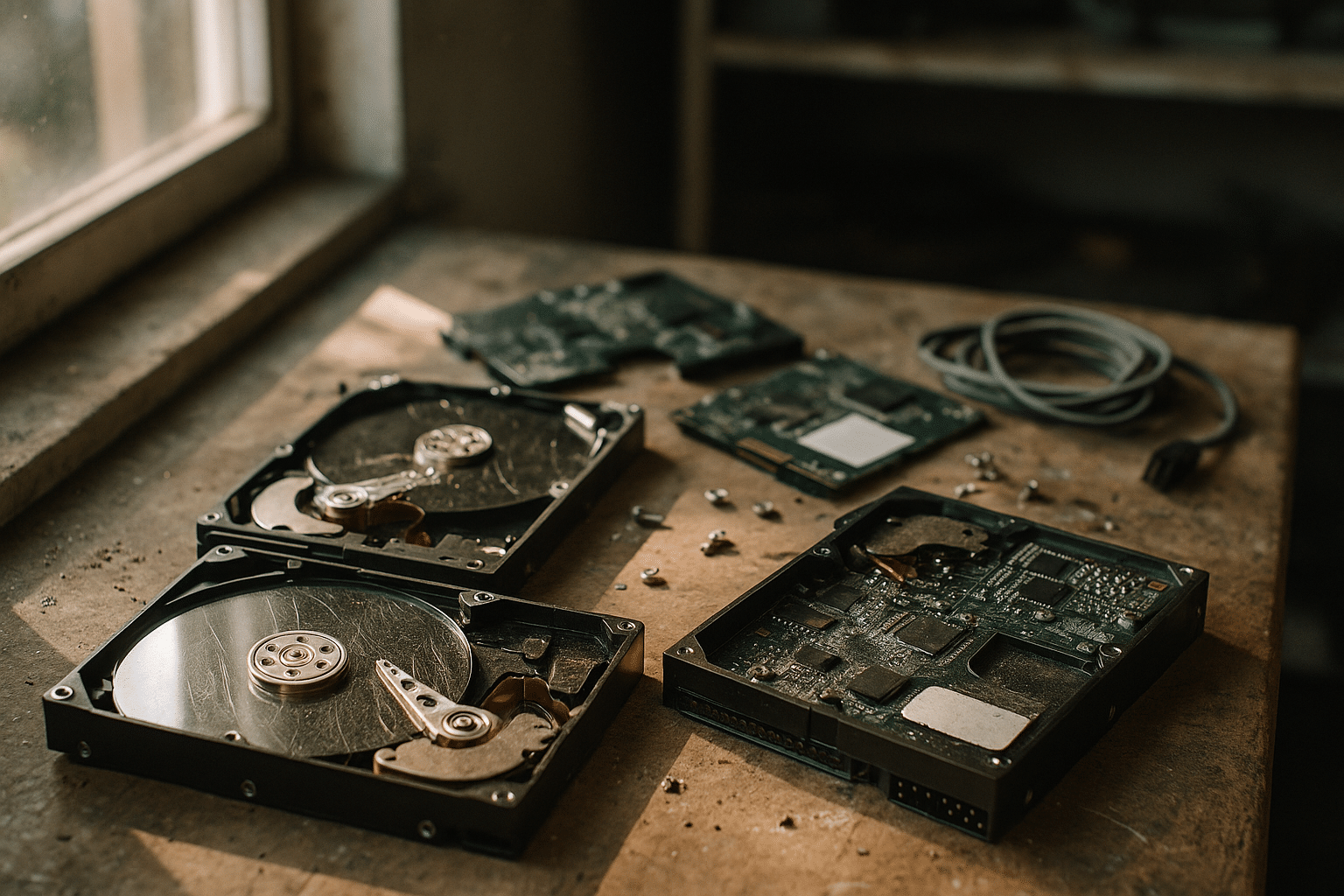

Storage Media: From Spinning Disks to Solid State and Tape

Not all bytes travel at the same pace or price. Spinning disks (HDDs) store data magnetically on rotating platters, offering generous capacity and friendly cost per gigabyte. Typical random access latency lands around 4–12 ms with 75–250 IOPS per drive, while sequential throughput often spans roughly 150–280 MB/s for common rotations and densities. They sip power modestly at idle yet draw more under heavy seeks, and their acoustic and vibration profile can matter in dense enclosures. For workloads dominated by large, sequential reads—log archives, streaming media, nightly ETL—HDDs remain a solid fit.

Solid-state drives (SSDs) drop the mechanical delays and deliver leapfrog responsiveness. Consumer-grade SATA SSDs commonly hit 500–550 MB/s sequentially with sub-millisecond latency; enterprise NVMe drives push into multi-gigabytes per second and tens of microseconds latency under favorable queue depths. Random read IOPS can range from tens of thousands to several hundred thousand, depending on interface lanes and controller design. Endurance varies with cell type: approximate program/erase expectations often move from higher durability to lower as density increases—SLC (very high), MLC (thousands of cycles), TLC (hundreds to low thousands), and QLC (double digits to low hundreds of cycles)—with effective lifespan shaped by write amplification, over-provisioning, and workload patterns. SSDs shine for transactional databases, virtual desktop bursts, search indices, and hot analytic queries where tail latency matters.

Tape is slower to access but efficient for cold retention. Access times may span tens of seconds to minutes due to loading and seeking, yet sustained transfer per drive can be competitive (often hundreds of MB/s). Under controlled storage conditions, cartridges can offer long shelf lives and favorable cost per terabyte at scale. For compliance archives, infrequent retrieval datasets, and air-gap strategies, tape remains relevant, especially when paired with cataloging software and disciplined labeling practices.

Practical buying signals:

– If your workload is random-write heavy with strict latency SLOs, steer toward NVMe SSD tiers and plan for write endurance.

– If your data is read-mostly, sequential, and warm rather than hot, large HDD pools with a small SSD cache can hit a sweet cost-to-performance ratio.

– If you need immutable, low-touch retention with minimal operating cost, consider tape as an archive layer with clear retrieval SLAs.

Energy and thermals also matter. SSDs typically run cooler per IOPS delivered, while HDDs can be more energy-efficient per stored byte. Tape, sitting mostly idle, is frugal at rest. Match physics to purpose and you’ll avoid overpaying for performance you won’t use—or underbuilding a system that later limps under load.

Architectures and Data Models: Block, File, and Object

How you access data shapes how you design for it. Block storage presents raw volumes addressed by fixed-size blocks; operating systems layer filesystems on top. It’s favored for databases and virtual machine disks that benefit from consistent, low latency and predictable I/O scheduling. File storage organizes data into hierarchical directories and files, balancing shareability with human-readable paths. It’s familiar, collaborative, and straightforward for home directories, content repos, and analytic staging areas. Object storage treats data as immutable objects with rich metadata in a flat namespace; clients interact via APIs, not mounts. It excels at scale, parallelism, and cost-effective durability across many nodes and sites.

Deployment models influence performance and manageability. Direct-attached storage (DAS) keeps media close to compute, minimizing hops and often maximizing single-host performance at the expense of poolability. Network-attached storage (NAS) serves files over the network, making shared datasets easier to manage and back up. Storage area networks (SANs) expose block volumes over dedicated fabrics, centralizing capacity while offering fine-grained performance isolation. Scale-up architectures grow by adding capacity to a controller pair; scale-out architectures add nodes, pushing capacity and throughput in lockstep.

Consistency, concurrency, and metadata policies differ. Object systems commonly offer eventual consistency for some operations, trading instantaneous global agreement for throughput and resilience; many now support stronger guarantees for specific actions. File systems arbitrate locks and handle simultaneous writers, which can introduce complexity at scale. Block devices defer coherence to the host and clustered filesystems layered above them. Your application’s read/write pattern and tolerance for delayed visibility should guide the model.

When to use what:

– Block: latency-sensitive databases, virtualized workloads, transactional systems needing steady IOPS and tight control over queues.

– File: shared analytics sandboxes, media repositories, collaborative engineering assets, and workflows with many mid-sized files.

– Object: data lakes, backups, logs, machine learning artifacts, and static web assets where horizontal scale and metadata-driven retrieval shine.

Finally, protection schemes bind to architecture. RAID is common in block and file arrays; erasure coding is prevalent in object clusters for space-efficient durability across failure domains. Think of architecture as the roadway, data model as the traffic rules, and protection as the guardrails—aligned, you cruise; misaligned, you hit potholes you could have paved over.

Durability, Protection, Security, and Governance

Durability isn’t a single feature; it’s a layered habit. Start with local fault tolerance: mirroring (RAID 1) protects against a single device failure; parity schemes (RAID 5/6) balance capacity and resilience; striped mirrors (RAID 10) trade capacity for speed and rebuild safety. As drive sizes grow, rebuild times stretch, and the chance of encountering an unrecoverable read error during a rebuild rises. That’s why scrubbing (periodic verification), end-to-end checksums, and proactive replacement policies are essential companions to RAID math.

For scale-out systems, erasure coding spreads fragments across nodes and racks, allowing recovery even when multiple components fail. Compared with mirroring, it often reduces capacity overhead for similar durability targets, at the cost of CPU and network during reconstruction. Snapshots capture point-in-time states with minimal overhead for incremental changes; they’re your first line against accidental deletes and bad deploys.

Backups remain non-negotiable. The 3-2-1 guideline—three copies of data, on two different media types, with one offsite—still holds. Modern refinements add immutability windows to defeat ransomware and operational mistakes. Replication strategies round it out: synchronous copies aim for near-zero data loss but require low-latency links; asynchronous replication tolerates lag while smoothing distance and bandwidth constraints. Define recovery point objective (RPO) and recovery time objective (RTO) per application, then test them with realistic drills, not just checklists.

Security travels with the data. Use encryption at rest with proven algorithms and rotate keys on a schedule tied to policy and risk. Protect keys with hardware modules or dedicated services, segregate duties so no single operator can both access and erase, and log every administrative action. In transit, enable encryption on all client and replication paths, and require mutual authentication for administrative endpoints. Least privilege should apply to both humans and machines; automated workflows need scoped tokens with short lifetimes.

Governance closes the loop. Data classification dictates retention, locality, and access rules; not every dataset needs the same rigor, but regulated records demand predictable handling. Implement lifecycle policies that transition objects from hot to warm to cold storage as they age, and codify holds for legal matters. Audit trails should be tamper-evident and searchable, with alerts for unusual patterns. You don’t need perfection—just a system that fails safely, recovers gracefully, and leaves a trail you can learn from.

Scalability, Performance, and Cost: Decision Framework and Conclusion

Scale arrives in waves, not steps, so treat capacity and performance as continuous tuning. Start with workload profiles: random versus sequential, read/write mix, request size, concurrency, and tail latency sensitivity. IOPS measures how many operations you can push; throughput is bulk transfer; latency is the time between request and response, with p95 and p99 tails telling the story your users actually feel. Watch queue depth and block sizes—changing one can dramatically alter the others.

Caching and tiering are your levers. Write-back caches can accelerate small writes but require persistent staging and safe eviction; write-through reduces risk at the cost of speed. Read caches help hot sets, but only if your hit rate stays high; measure before declaring victory. Tiering moves data across SSD, HDD, and tape based on age or access patterns. Lifecycle rules can demote cold objects automatically, shrinking spend without impeding retrievals that can wait a bit longer.

Observability is an early warning system. Track device health, error rates, rebuild times, saturation signals, and end-to-end latency across the stack. Correlate application metrics with storage counters to catch head fakes—sometimes the bottleneck is a chatty client, not the array. Capacity planning blends trend lines with human context: upcoming features, seasonality, and compliance mandates. A simple model helps: estimate growth in storage (GB/month), IOPS per workload, and bandwidth per peak minute; add buffers for variance; then test with synthetic and production-like load.

Cost deserves a dual lens: price per stored GB and price per delivered IOPS/latency. An inexpensive archive tier might be perfect for logs but painful for interactive analytics. Factor power, cooling, floor space, and operational overhead into total cost of ownership; the cheapest terabyte can be costly if it requires constant babysitting. Efficiency tips:

– Right-size volumes and avoid tiny, fragmented files when a grouped format would reduce metadata churn.

– Compress and deduplicate where it helps more than it hurts CPU budgets.

– Align data layout with access patterns to reduce seeks and cache misses.

Decision framework: define SLOs (latency, durability, availability), inventory data temperature (hot, warm, cold), map workloads to access models (block/file/object), select media tiers, then layer protection and lifecycle policies. Pilot on a subset, measure, adjust, roll out. You’re aiming for a posture that is resilient by default and frugal by design.

Conclusion: For builders, operators, and data owners, storage isn’t just where bits live—it’s where reliability, speed, and cost negotiate daily. Choose media that matches physics to need, architectures that fit access patterns, and protections that assume failure will eventually knock. With clear SLOs, honest measurements, and iterative tuning, your data platform will carry today’s traffic and tomorrow’s surprises without drama—and that quiet reliability is the real headline.